how to explain what magic mushrooms look like

Psilocybin mushrooms; commonly known as magic mushrooms, mushrooms or shrooms, are an polyphyletic informal group of fungi that contain psilocybin which turns into psilocin upon ingestion.[ane] [2] Biological genera containing psilocybin mushrooms include Copelandia, Gymnopilus, Inocybe, Panaeolus, Pholiotina, Pluteus, and Psilocybe. Psilocybin mushrooms have been and go on to exist used in ethnic New World cultures in religious, divinatory, or spiritual contexts.[3] Psilocybin mushrooms are too used every bit recreational drugs. They may be depicted in Stone Age stone fine art in Africa and Europe, but are most famously represented in the Pre-Columbian sculptures and glyphs seen throughout North, Central and S America.

History [edit]

Early [edit]

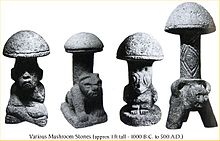

Pre-Columbian mushroom stones

Prehistoric rock arts near Villar del Humo in Kingdom of spain, suggests that Psilocybe hispanica was used in religious rituals 6,000 years ago.[4] The hallucinogenic[5] species of the Psilocybe genus have a history of apply amongst the native peoples of Mesoamerica for religious communion, divination, and healing, from pre-Columbian times to the nowadays day.[vi] Mushroom stones and motifs have been plant in Guatemala.[7] A statuette dating from ca. 200 CE. depicting a mushroom strongly resembling Psilocybe mexicana was found in the west Mexican country of Colima in a shaft and chamber tomb. A Psilocybe species known to the Aztecs as teōnanācatl (literally "divine mushroom": adhesive course of teōtl (god, sacred) and nanācatl (mushroom) in Nahuatl language) was reportedly served at the coronation of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma Ii in 1502. Aztecs and Mazatecs referred to psilocybin mushrooms every bit genius mushrooms, divinatory mushrooms, and wondrous mushrooms, when translated into English.[8] Bernardino de Sahagún reported the ritualistic use of teonanácatl past the Aztecs when he traveled to Central America after the expedition of Hernán Cortés.[9]

After the Spanish conquest, Catholic missionaries campaigned against the cultural tradition of the Aztecs, dismissing the Aztecs as idolaters, and the employ of hallucinogenic plants and mushrooms, together with other pre-Christian traditions, was chop-chop suppressed.[vii] The Spanish believed the mushroom allowed the Aztecs and others to communicate with demons. Despite this history the use of teonanácatl has persisted in some remote areas.[3]

Modern [edit]

The first mention of hallucinogenic mushrooms in European medicinal literature was in the London Medical and Physical Journal in 1799: a human being served Psilocybe semilanceata mushrooms he had picked for breakfast in London'south Green Park to his family unit. The apothecary who treated them subsequently described how the youngest child "was attacked with fits of immoderate laughter, nor could the threats of his father or mother refrain him."[x]

In 1955, Valentina Pavlovna Wasson and R. Gordon Wasson became the first known European Americans to actively participate in an ethnic mushroom ceremony. The Wassons did much to publicize their experience, even publishing an article on their experiences in Life on May 13, 1957.[11] In 1956, Roger Heim identified the psychoactive mushroom the Wassons brought back from Mexico every bit Psilocybe,[12] and in 1958, Albert Hofmann first identified psilocybin and psilocin equally the active compounds in these mushrooms.[13] [14]

Inspired by the Wassons' Life article, Timothy Leary traveled to United mexican states to feel psilocybin mushrooms himself. When he returned to Harvard in 1960, he and Richard Alpert started the Harvard Psilocybin Project, promoting psychological and religious report of psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs. Alpert and Leary sought out to acquit research with psilocybin on prisoners in the 1960s, testing its effects on recidivism.[15] This experiment reviewed the subjects half dozen months later, and establish that the recidivism rate had decreased beyond their expectation, beneath 40%. This, and some other experiment administering psilocybin to graduate divinity students, showed controversy. Before long after Leary and Alpert were dismissed from their jobs by Harvard in 1963, they turned their attention toward promoting the psychedelic experience to the nascent hippie counterculture.[16]

The popularization of entheogens by the Wassons, Leary, Terence McKenna, Robert Anton Wilson and many others led to an explosion in the use of psilocybin mushrooms throughout the earth. By the early on 1970s, many psilocybin mushroom species were described from temperate North America, Europe, and Asia and were widely nerveless. Books describing methods of cultivating large quantities of Psilocybe cubensis were also published. The availability of psilocybin mushrooms from wild and cultivated sources take fabricated them one of the most widely used of the psychedelic drugs.

At present, psilocybin mushroom apply has been reported among some groups spanning from primal Mexico to Oaxaca, including groups of Nahua, Mixtecs, Mixe, Mazatecs, Zapotecs, and others.[three] An important figure of mushroom usage in Mexico was María Sabina,[17] who used native mushrooms, such every bit Psilocybe mexicana in her practice.

Occurrence [edit]

In a 2000 review on the worldwide distribution of psilocybin mushrooms, Gastón Guzmán and colleagues considered these distributed among the following genera: Psilocybe (116 species), Gymnopilus (14), Panaeolus (13), Copelandia (12), Pluteus (half dozen) Inocybe (6), Pholiotina (4) and Galerina (1).[18] Guzmán increased his judge of the number of psilocybin-containing Psilocybe to 144 species in a 2005 review.

Global distribution of 100+ psychoactive species of genus Psilocybe mushrooms.[19]

Many of them are institute in Mexico (53 species), with the remainder distributed throughout Canada and the US (22), Europe (16), Asia (xv), Africa (4), and Commonwealth of australia and associated islands (nineteen).[20] Mostly, psilocybin-containing species are dark-spored, gilled mushrooms that grow in meadows and woods in the subtropics and torrid zone, unremarkably in soils rich in humus and plant droppings.[21] Psilocybin mushrooms occur on all continents, but the bulk of species are found in subtropical humid forests.[xviii] P. cubensis is the virtually common Psilocybe in tropical areas. P. semilanceata, considered the world's almost widely distributed psilocybin mushroom,[22] is found in temperate parts of Europe, North America, Asia, South America, Australia and New Zealand, although it is absent-minded from United mexican states.[twenty]

Composition [edit]

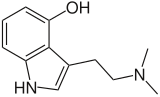

Magic mushroom composition varies from genus to genus and species to species.[23] Its principal component is psilocybin[24] which gets converted into psilocin to produce psychoactive effect. Besides, psilocin, norpsilocin, baeocystin, norbaeocystin and aeruginascin may too be present which can modify the furnishings of magic mushrooms.[23] Panaeolus subbalteatus, one of magic mushroom, had highest amount of psilocybin compared to the rest of the fruiting trunk.[23] Certain mushrooms are found to produce beta carbolines which inhibits monoamine oxidase, an enzyme which breaks down tryptamine alkaloids.[25] They occur in unlike genera, like Psilocybe,[26] Cyclocybe [27] and Hygrophorus [28] Harmine, harmane, norharmane and a range of other l-tryptophan-derived β-carbolines were discovered in Psilocybe species.

Effects [edit]

The effects of psilocybin mushrooms come from psilocybin and psilocin. When psilocybin is ingested, it is broken down by the liver in a process called dephosphorylation. The resulting chemical compound is chosen psilocin, which is responsible for the psychedelic effects.[29] Psilocybin and psilocin create brusk-term increases in tolerance of users, thus making information technology difficult to misuse them because the more often they are taken within a short period of time, the weaker the resultant effects are.[30] Psilocybin mushrooms have not been known to crusade physical or psychological dependence (addiction).[31] The psychedelic furnishings tend to appear effectually xx minutes subsequently ingestion and can last up to 6 hours. Physical effects including nausea, airsickness, euphoria, musculus weakness or relaxation, drowsiness, and lack of coordination may occur.

As with many psychedelic substances, the effects of psychedelic mushrooms are subjective and tin vary considerably among individual users. The listen-altering effects of psilocybin-containing mushrooms typically last from three to eight hours depending on dosage, preparation method, and personal metabolism. The first 3–iv hours subsequently ingestion are typically referred to as the 'peak'—in which the user experiences more brilliant visuals and distortions in reality. The effects can seem to last much longer to the user because of psilocybin's ability to change time perception.[32]

Despite risks, mushrooms do much less damage in the UK than other recreational drugs.

Sensory [edit]

Sensory effects include visual and auditory hallucinations followed by emotional changes and altered perception of time and infinite.[33] Noticeable changes to the auditory, visual, and tactile senses may become credible effectually 30 minutes to an hour after ingestion, although effects may take up to two hours to take identify. These shifts in perception visually include enhancement and contrasting of colors, strange light phenomena (such as auras or "halos" around calorie-free sources), increased visual acuity, surfaces that seem to ripple, shimmer, or breathe; complex open up and closed eye visuals of grade constants or images, objects that warp, morph, or change solid colours; a sense of melting into the environment, and trails behind moving objects. Sounds may seem to accept increased clarity—music, for example, can take on a profound sense of cadence and depth.[33] Some users experience synesthesia, wherein they perceive, for example, a visualization of color upon hearing a particular sound.[34]

Emotional [edit]

As with other psychedelics such every bit LSD, the experience, or 'trip', is strongly dependent upon set and setting.[33] Hilarity, lack of concentration, and muscular relaxation (including dilated pupils) are all normal effects, sometimes in the same trip.[33] A negative environment could contribute to a bad trip, whereas a comfortable and familiar environment would set the phase for a pleasant experience. Psychedelics make experiences more intense, so if a person enters a trip in an anxious state of mind, they will likely experience heightened feet on their trip. Many users detect it preferable to ingest the mushrooms with friends or people who are familiar with 'tripping'.[35] The psychological consequences of psilocybin utilise include hallucinations and an inability to discern fantasy from reality. Panic reactions and psychosis also may occur, particularly if a user ingests a large dose. In addition to the risks associated with ingestion of psilocybin, individuals who seek to use psilocybin mushrooms also risk poisoning if one of the many varieties of poisonous mushrooms is confused with a psilocybin mushroom.[36]

Dosage [edit]

A bag of one.5 grams of stale psilocybe cubensis mushrooms.

Dosage of mushrooms containing psilocybin depends on the psilocybin and psilocin content of the mushroom which tin can vary significantly between and within the same species, but is typically around 0.5–two.0% of the dried weight of the mushroom. Usual doses of the common species Psilocybe cubensis range around 1.0 to 2.v g,[37] while about 2.v to five.0 g[37] dried mushroom material is considered a strong dose. Above v g is oft considered a heavy dose with 5.0 grams of dried mushroom often beingness referred to as a "heroic dose".[38] [39]

The concentration of active psilocybin mushroom compounds varies from species to species, but besides from mushroom to mushroom inside a given species, subspecies or diverseness. The aforementioned holds true for different parts of the aforementioned mushroom. In the species Psilocybe samuiensis, the dried cap of the mushroom contains the about psilocybin at virtually 0.23%–0.90%. The mycelium contains near 0.24%–0.32%.[40] Drinking a mushroom tea is easier on the breadbasket than consuming the difficult to digest, raw mushroom material, such as chitin which makes upwards fungi's cell walls.[41]

Inquiry [edit]

Due partly to restrictions of the Controlled Substances Human action in the Usa, inquiry had been frozen until the early 21st century when psilocybin mushrooms were tested for their potential to treat drug dependence, anxiety and mood disorders.[42] In 2018–19, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation for studies of psilocybin in depressive disorders.[43]

A written report at Johns Hopkins University found that a dose of 20 to 30 mg psilocybin per 70 kg occasioning mystical-type experiences brought lasting positive changes to traits including altruism, gratitude, forgiveness and feeling shut to others when it was combined with meditation and an extensive spiritual practice support programme.[44] [45] There is scientific evidence for a context- and state-dependent causal effect of psychedelic use on connection with nature.[46]

Legality [edit]

The legality of the cultivation, possession, and sale of psilocybin mushrooms and of psilocybin and psilocin varies from state to country.

See also [edit]

- Magic truffle

- Listing of psilocybin mushroom species

- List of psychoactive plants, fungi, and animals

- Entheogenic drugs and the archaeological record

- Psychedelic (disambiguation)

- Psilocybin decriminalization in the United States

- Psychonautics

- Mystical psychosis

- Ethnomycology

- Medicinal fungi

- Mushroom tea

- Carlos Castaneda

- Paul Stamets

References [edit]

- ^ Kuhn, Cynthia; Swartzwelder, Scott; Wilson, Wilkie (2003). Buzzed: The Straight Facts about the Near Used and Abused Drugs from Booze to Ecstasy. W.West. Norton & Company. p. 83. ISBN978-0-393-32493-8.

- ^ Canada, Wellness (January 12, 2012). "Magic mushrooms – Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Archived from the original on Dec 22, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c Guzmán G. (2008). "Hallucinogenic mushrooms in Mexico: An overview". Economic Botany. 62 (iii): 404–412. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9033-8. S2CID 22085876.

- ^ Akers, Brian P.; Ruiz, Juan Francisco; Piper, Alan; Ruck, Carl A. P. (2011). "A Prehistoric Mural in Spain Depicting Neurotropic Psilocybe Mushrooms?one". Economic Botany. 65 (ii): 121–128. doi:ten.1007/s12231-011-9152-5. S2CID 3955222.

- ^ Abuse, National Establish on Drug (April 22, 2019). "Hallucinogens DrugFacts". National Institute on Drug Corruption . Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ F.J. Carod-Artal (January 1, 2015). "Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures". Neurología (English Edition). 30 (one): 42–49. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2011.07.010. PMID 21893367.

- ^ a b Stamets (1996), p. 11.

- ^ Stamets (1996), p. vii.

- ^ Hofmann A. (1980). "The Mexican relatives of LSD". LSD: My Problem Child. New York City: McGraw-Hill. pp. 49–71. ISBN978-0-07-029325-0.

- ^ Brande E. (1799). "Mr. E. Brande, on a poisonous species of Agaric". The Medical and Concrete Journal: Containing the Earliest Information on Subjects of Medicine, Surgery, Pharmacy, Chemical science and Natural History. 3 (11): 41–44. PMC5659401. PMID 30490162.

- ^ Wasson RG (1957). "Seeking the magic mushroom". Life. No. May 13. pp. 100–120. article reproduced online

- ^ Heim R. (1957). "Notes préliminaires sur les agarics hallucinogènes du Mexique" [Preliminary notes on the hallucination-producing agarics of United mexican states]. Revue de Mycologie (in French). 22 (1): 58–79.

- ^ Hofmann A, Frey A, Ott H, Petrzilka T, Troxler F (1958). "Konstitutionsaufklärung und Synthese von Psilocybin" [The composition and synthesis of psilocybin]. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (in German language). 14 (11): 397–399. doi:x.1007/BF02160424. PMID 13609599. S2CID 33692940.

- ^ Hofmann A, Heim R, Brack A, Kobel H (1958). "Psilocybin, ein psychotroper Wirkstoff aus dem mexikanischen Rauschpilz Psilocybe mexicana Heim" [Psilocybin, a psychotropic drug from the Mexican magic mushroom Psilocybe mexicana Heim]. Experientia (in German). 14 (3): 107–109. doi:10.1007/BF02159243. PMID 13537892. S2CID 42898430.

- ^ "Dr. Leary'southward Concord Prison Experiment: A 34 Yr Follow-Up Study". Bulletin of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. 9 (4): 10–eighteen. 1999.

- ^ Lattin, Don (2010). The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil killed the fifties and ushered in a new age for America (1st ed.). New York: HarperOne. pp. 37–44. ISBN978-0-06-165593-7.

- ^ Monaghan, John D.; Cohen, Jeffrey H. (2000). "Xxx years of Oaxacan ethnography". In Monaghan, John; Edmonson, Barbara (eds.). Ethnology. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 165. ISBN978-0-292-70881-5.

- ^ a b Guzmán, G.; Allen, J.W.; Gartz, J. (2000). "A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi, an analysis and give-and-take" (PDF). Annali del Museo Civico di Rovereto: Sezione Archeologia, Storia, Scienze Naturali. 14: 189–280.

- ^ Guzmán M, Allen JW, Gartz J (1998). "A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi, an analysis and discussion" (PDF). Annali del Museo Civico di Rovereto. 14: 207.

- ^ a b Guzmán, Chiliad. (2005). "Species diversity of the genus Psilocybe (Basidiomycotina, Agaricales, Strophariaceae) in the world mycobiota, with special attending to hallucinogenic backdrop". International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 7 (1–2): 305–331. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushr.v7.i12.280.

- ^ Wurst, K.; Kysilka, R.; Flieger, M. (2002). "Psychoactive tryptamines from Basidiomycetes". Folia Microbiologica. 47 (1): 3–27 [5]. doi:10.1007/BF02818560. PMID 11980266. S2CID 31056807.

- ^ Guzmán, 1000. (1983). The Genus Psilocybe: A Systematic Revision of the Known Species Including the History, Distribution, and Chemistry of the Hallucinogenic Species. Beihefte Zur Nova Hedwigia. Vol. 74. Vaduz, Liechtenstein: J. Cramer. pp. 361–ii. ISBN978-three-7682-5474-viii.

- ^ a b c "Chemical Limerick Variability in Magic Mushrooms". March 4, 2019.

- ^ "Hallucinogenic mushrooms drug profile". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

- ^ "Psilocybin Isn't the Only Compound in Magic Mushrooms—Here's What Else There Is".

- ^ Blei F, Dörner South, Fricke J, Baldeweg F, Trottmann F, Komor A, Meyer F, Hertweck C, Hoffmeister D (January 2020). "Simultaneous Production of Psilocybin and a Cocktail of β-Carboline Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors in "Magic" Mushrooms". Chemistry—A European Periodical. 26 (three): 729–734. doi:10.1002/chem.201904363. PMC7003923. PMID 31729089.

- ^ Krüzselyi D, Vetter J, Ott PG, Darcsi A, Béni S, Gömöry Á, Drahos L, Zsila F, Móricz ÁM (September 2019). "Isolation and structural elucidation of a novel brunnein-type antioxidant β-carboline alkaloid from Cyclocybe cylindracea". Fitoterapia. 137: 104180. doi:x.1016/j.fitote.2019.104180. PMID 31150766. S2CID 172137046.

- ^ Teichert A, Lübken T, Schmidt J, Kuhnt C, Huth M, Porzel A, Wessjohann 50, Arnold N (2008). "Determination of beta-carboline alkaloids in fruiting bodies of Hygrophorus spp. by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry". Phytochemical Analysis. xix (four): 335–41. doi:10.1002/pca.1057. PMID 18401852.

- ^ Passie, T.; Seifert, J.; Schneider, und; Emrich, H.M. (2002). "The pharmacology of psilocybin". Addiction Biology. 7 (4): 357–364. doi:10.1080/1355621021000005937. PMID 14578010. S2CID 12656091.

- ^ "Psilocybin Fast Facts". National Drug Intelligence Center. Retrieved April iv, 2007.

- ^ van Amsterdam, J.; Opperhuizen, A.; van den Brink, W. (2011). "Harm potential of magic mushroom use: A review". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 59 (3): 423–429. doi:x.1016/j.yrtph.2011.01.006. PMID 21256914.

- ^ Wittmann, M.; Carter, O.; Hasler, F.; Cahn, B.R.; Grimberg, und; Bound, P.; Hell, D.; Flohr, H.; Vollenweider, F.Ten. (2007). "Furnishings of psilocybin on time perception and temporal command of behaviour in humans". Periodical of Psychopharmacology. 21 (one): 50–64. doi:10.1177/0269881106065859. PMID 16714323. S2CID 3165579.

- ^ a b c d Schultes, Richard Evans (1976). Hallucinogenic Plants. Illustrated by Elmer W. Smith. New York: Aureate Printing. p. 68. ISBN978-0-307-24362-1.

- ^ Ballesteros, S.; Ramón, Chiliad.F.; Iturralde, K.J.; Martínez-Arrieta, R. (2006). "Natural Sources of Drugs of Corruption: Magic Mushrooms". In Cole, S.1000. (ed.). New Research on Street Drugs. Nova Scientific discipline Publishers. p. 175. ISBN978-1-59454-961-8.

- ^ Stamets (1996)

- ^ "Psilocybin Fast Facts". National Drug Intelligence Eye, US Department of Justice. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain .

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain . - ^ a b Erowid (2006). "Dosage Nautical chart for Psychedelic Mushrooms" (shtml). Erowid. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ^ "Terence McKenna's Last Trip". Wired Magazine. Condé Nast Publications. May 1, 2000. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Jesso, James West. (June 13, 2013). Decomposing The Shadow: Lessons From The Psilocybin Mushroom. SoulsLantern Publishing. p. xc. ISBN978-0-9919435-0-0 . Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Gartz J, Allen JW, Merlin MD (2004). "Ethnomycology, biochemistry, and cultivation of Psilocybe samuiensis Guzmán, Bandala and Allen, a new psychoactive fungus from Koh Samui, Thailand". Periodical of Ethnopharmacology. 43 (ii): 73–80. doi:x.1016/0378-8741(94)90006-Ten. PMID 7967658.

- ^ Janikian, Michelle (November 4, 2021). "How to Make Shroom Tea: The Ultimate Mushroom Tea Guide". DoubleBlind Mag . Retrieved Jan 6, 2022.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bui, Eric; King, Franklin; Melaragno, Andrew (December 1, 2019). "Pharmacotherapy of feet disorders in the 21st century: A call for novel approaches (Review)". General Psychiatry. 32 (half-dozen): e100136. doi:ten.1136/gpsych-2019-100136. PMC6936967. PMID 31922087.

- ^ "FDA grants Breakthrough Therapy Designation to Usona Found'due south psilocybin program for major depressive disorder". www.businesswire.com. November 22, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Griffiths, Roland R.; et al. (October 2017). "Psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces indelible positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 32 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1177/0269881117731279. PMC5772431. PMID 29020861.

- ^ "Psilocybin (from magic mushrooms) plus meditation and spiritual preparation leads to lasting changes in positive traits". Research Digest. January 19, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Kettner, Hannes; Gandy, Sam; Haijen, Eline C. H. M.; Carhart-Harris, Robin L. (Dec sixteen, 2019). "From Egoism to Ecoism: Psychedelics Increase Nature Relatedness in a Land-Mediated and Context-Dependent Manner". International Periodical of Environmental Research and Public Health. sixteen (24): 5147. doi:10.3390/ijerph16245147. PMC6949937. PMID 31888300.

Bibliography [edit]

- Allen, J.W. (1997). Magic Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Raver Books and John Westward. Allen. ISBN978-one-58214-026-1.

- Estrada, A. (1981). Maria Sabina: Her Life and Chants. Ross Erikson. ISBN978-0-915520-32-nine.

- Haze, Virginia & Dr. Chiliad. Mandrake, PhD. The Psilocybin Mushroom Bible: The Definitive Guide to Growing and Using Magic Mushrooms. Light-green Candy Press: Toronto, Canada, 2016. ISBN 978-i-937866-28-0. www.greencandypress.com.

- Högberg, O. (2003). Flugsvampen och människan (in Swedish). ISBN978-91-7203-555-iii.

- Kuhn, C.; Swartzwelder, Southward; Wilson, Westward. (2003). Buzzed: The Straight Facts about the Nearly Used and Driveling Drugs from Alcohol to Ecstasy . New York: W.Westward. Norton & Visitor. ISBN978-0-393-32493-8.

- Letcher, A. (2006). Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN978-0-571-22770-9.

- McKenna, T. (1993). Food of the Gods. Bantam. ISBN978-0-553-37130-7.

- Nicholas, L.G.; Ogame, K. (2006). Psilocybin Mushroom Handbook: Easy Indoor and Outdoor Tillage. Quick American Archives. ISBN978-0-932551-71-9.

- Stamets, P. (1993). Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. ISBN978-1-58008-175-7.

- Stamets, P.; Chilton, J.S. (1983). The Mushroom Cultivator. Olympia: Agarikon Press. ISBN978-0-9610798-0-ii.

- Stamets, P. (1996). Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World. Berkeley: X Speed Press. ISBN978-0-9610798-0-two.

- Wasson, G.R. (1980). The Wondrous Mushroom: Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. McGraw-Hill. ISBN978-0-07-068443-0.

External links [edit]

![]() The dictionary definition of magic mushroom at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of magic mushroom at Wiktionary

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psilocybin_mushroom